I flew into Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, from Semey. It has a new name, Nur-Sultan, in honour President Nursultan Nazarbayev, who has recently abdicated. For me, though, it remains Astana.

I haven’t read a single article or blog that has not used the words ‘weird’ or ‘strange’ to describe the city of Astana. This planned city, is Nazarbayev’s idiosyncratic display of splendour and power, and an attempt to propel Kazakhstan up the twin ladders of Eurasian leadership and global recognition.

Astana, to some, may appear like a sci-fi set, and is a mix of Dubai, Brasilia and Russian orthodox townships. It’s hyper-modern buildings bend and warp at impossible angles, their claddings of metal and glass shimmer in the sunlight, and their imposing heights want to lay claim to slivers of the blue sky. The entire city fans out on both sides of the Ishim river; but it’s location in the middle of brown-green steppe gives it a starkness that borders on the eerie.

Huge reserves of oil, natural gas and minerals provide the cash for such splurges on architectural extravagance and displays of pomp and ceremony. It is the richest country in Central Asia with a per-capita GDP that is higher than that of the Russian Federation. Its biggest export commodity is crude (45%) and its FDI inflows are from Netherlands, Switzerland and USA. Its focus on infrastructure building has brought in a slew of foreign consultants, architects, engineers, tech-experts, lawyers and teachers.

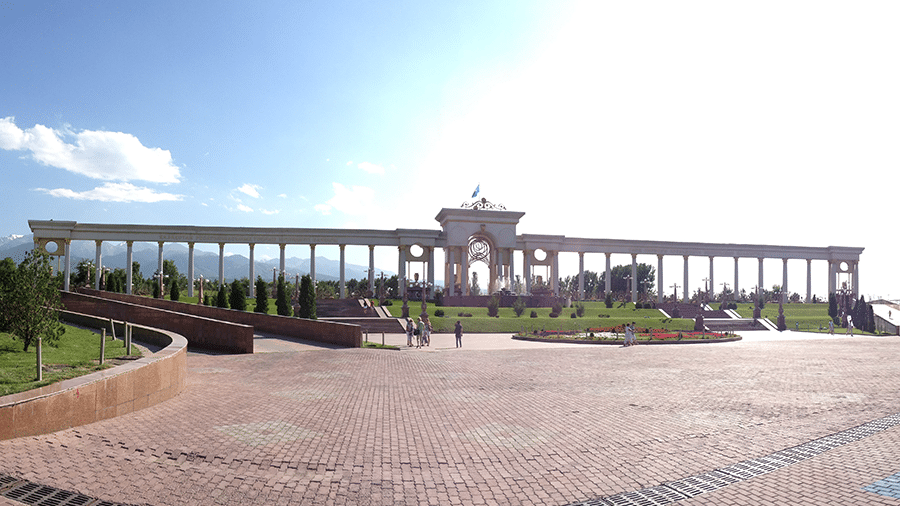

Despite the lack of an old-city charm and warmth (that Almaty has) there is much to see in Astana. It has museums (the best being, The National Museum of Kazakhstan), gardens, palaces, mosques, and synagogues. I went up the landmark tower of Baiterek, visited the Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, wondered at the Ak Orda Presidential Palace, walked on a beach (imported Maldivian sand) in the Khan Shatyr (world’s tallest tent shaped structure), and marvelled at the Nur-Astana Mosque.

It’s sad to see Kazakhs take the petro-dollar route to modernity but I can understand their need move away from a forgotten way of life, and fast-track their economy into global relevance.